|

launch interview with Ranjani Shettar

Having trained in sculpture at Chitrakala Institute of Advanced Studies in Bangalore, Ranjani Shettar creates three-dimensional works that explore the confrontation of the urban and the organic, the metaphysical and the mundane. Employing a wide range of common, everyday materials such as wax, India ink, paper, resin, cotton, PVC pipes, plastic sheeting, and mud, Shettar constructs sculptural artifacts that speak obliquely to the effects of urbanization in newly high-tech Bangalore. By using a formal language that invokes the organic and a material language that suggests the industrial, she operates in a manner similar to that of Bangalore itself, where industrial urbanization is colliding with (and collapsing into) the once rural countryside. But above all else, Shettar's work asks phe-nomenological questions about the way in which we inhabit particular spaces in our built environment.

The organic qualities of Shettar's work might be profitably read in the art-historical contexts of Arte Povera artist Marisa Merz, postminimalist sculptors of the same period such as Eva Hesse, Brazilian Neo-concrete artist Lygia Clark, or Argentinean artist Gego. Like these precursors, Shettar uses industrial materials at odds with the biomorphic qualities of her work, setting up a dichotomy between the man-made and the natural. Likewise, Shettar emerged within the context of a slightly more senior generation of Indian artists working in sculpture and installation, such as Sheela Gowda and Anita Dube, each of whom negotiates a terrain similar to that of the artists mentioned above but within a specifically Indian situation.

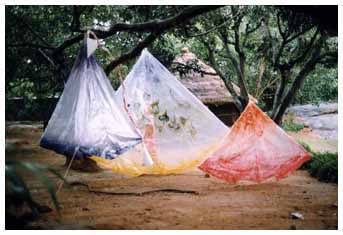

In her solo exhibition Home (2000), Shettar launched into a sculptural investigation of the concept of shelter. Employing a biological idiom in these works, the artist constructed a series of archetypal structures from nature that might be thought of as "homes," ranging from those of insects and birds to silkworms and even plants. Invitations, for example, is a series of pod- or cocoonlike resin forms that are piled rather haphazardly in a corner. Another work in this exhibition, Thousand Room House, is reminiscent of a beehive, although its strangely organic honeycomb structure is constructed with the decidedly artificial materials of plastic sheeting, rope, and rivets. Each of these works speaks to what philosopher Gaston Bachelard has described as an "intimate immensity," in that each structure invokes a shelter that is poetically suggestive of our oneiric ability to invest spaces with our own desires and phenomenological memories. As suggested by Bachelard, "A house that has been experienced is not an inert box. Inhabited space transcends geometrical space." Such a specificity of inhabited space, of the space of a shelter invested with a particular kind of living and spiritual energy, is operative in Shettar's work. As she herself suggests, "Home is the body. The body is not the physical alone but the mental, emotional and the spiritual." In all of her work, Shettar maintains this explicit dialogue between the spiritual and the everyday.

Shettar had a solo exhibition at the Chitra Art Gallery, Bangalore, India, in 2000. Her work has appeared in a number of group exhibitions, including On the Edge of Volume, curated by Martha Jakimowicz-Karle for Sakshi Gallery and Alliance Française, Bangalore (2001), and Concept Shop at Sakshi Gallery, Bangalore (2000).

--Douglas Fogle