|

launch interview with Song Dong

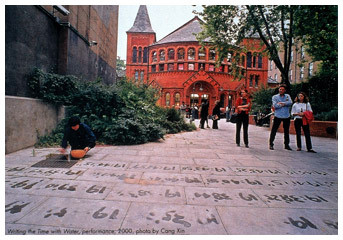

Song Dong's work embraces performance, video installation, calligraphy, sculpture, and site-specific projects. His strength lies in a capacity to summon or convene opposites. As he has stated, "I am interested in how the two sides of the East/West contradiction become one." Song attempts to relocate our experience of art to some place between modernity and tradition; past and present; Taoist philosophy and conceptual art traditions, first manifested in the 1960s, that privilege the process of construction or attainment over the finished product. For Song the root of all these activities, indeed of most human endeavor, is self-expression. Because of this, the audience is at times tangential, as in the example of his Water Diary (1995-present). This diary, written with water on stone, has become an integral part of his life. Although he has photographed this daily ritual for exhibition purposes, it is first and foremost a personal experience inspired by the memory of his own modestly lived childhood. In order to not waste precious paper and ink, Song's father encouraged him to use water on a stone to practice his calligraphy. As an artist, Song began writing his diary with water on a stone in 1995, and it became a way to release his emotions in absolute privacy, leaving no trace.

The evanescence that embodies his relation to art and to Taoism eventually led Song to work in video. The artist has said that "the medium of video is elemental. It produces moving images and sounds that cannot be touched. It has no shape but provides a strong light and can be projected onto any object." Song's video production seems to follow the same binary logic as his water writing. On the one hand, he explores larger social and cultural issues, as in Crumpling Shanghai (2000), which serves as a comment on the recent predatory urban development in China. On the other hand, his work explores very personal, intimate experiences. In Touching My Father (1998), he projected onto his father's body a video image of his own hand. In a culture that does not facilitate physical contact, touching his father in this way was a strong statement about the traditional relationship between fathers and sons as well as an attempt to bridge the generation gap that has appeared in China's recent development.

Whatever topic Song approaches, his critique always manages to walk the thin line between the politic and the poetic. Jump (1999), a performance during which he jumped aimlessly in front of the Forbidden City in Beijing, in the middle of the absolutely indifferent crowd, reveals the importance he places on both cerebral and physical experiences. Jump, with its Taoist absurdity, could find its roots in a traditional Chinese proverb: "Jump … no reason not to jump … no reason to jump." It crystallizes a sense of tradition, calls into play strategies sprung from a history of avant-garde performance work, emphasizes an aspect of the urban Chinese "everyday," and questions the status and visibility of art and culture in the world today.

Song has exhibited widely in Asia and abroad, including solo exhibitions in London and Beijing and group exhibitions in Germany, Korea, and the United States. He was included in Inside Out: New Chinese Art (1998), organized by the Asia Society Galleries, New York, and the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, California, and Transience: Chinese Art at the End of the 20th Century (1991), organized by the Smart Museum of Art in Chicago, Illinois. He also participated in the 2002 Gwangju Biennale, South Korea, and the Fourth Asia-Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art in Brisbane, Australia (2002).

--Philippe Vergne